(Pictures: Action Images via Reuters)

By Chris Dunlavy

MARK Lawrenson often tells the tale of his first Merseyside derby for Liverpool, a 3-1 victory at Goodison Park in the autumn of 1981.

For Ray Kennedy, that day marked his last such fixture. At 31, the European Cup winner and Kop legend knew he’d be leaving Anfield in January, a switch to Swansea under his old mate John Toshack all but sealed.

Sadly for Kennedy, his swansong lasted just half an hour. A shuddering challenge from Everton hardman Mick Lyons saw the stretcher-bearers summoned.

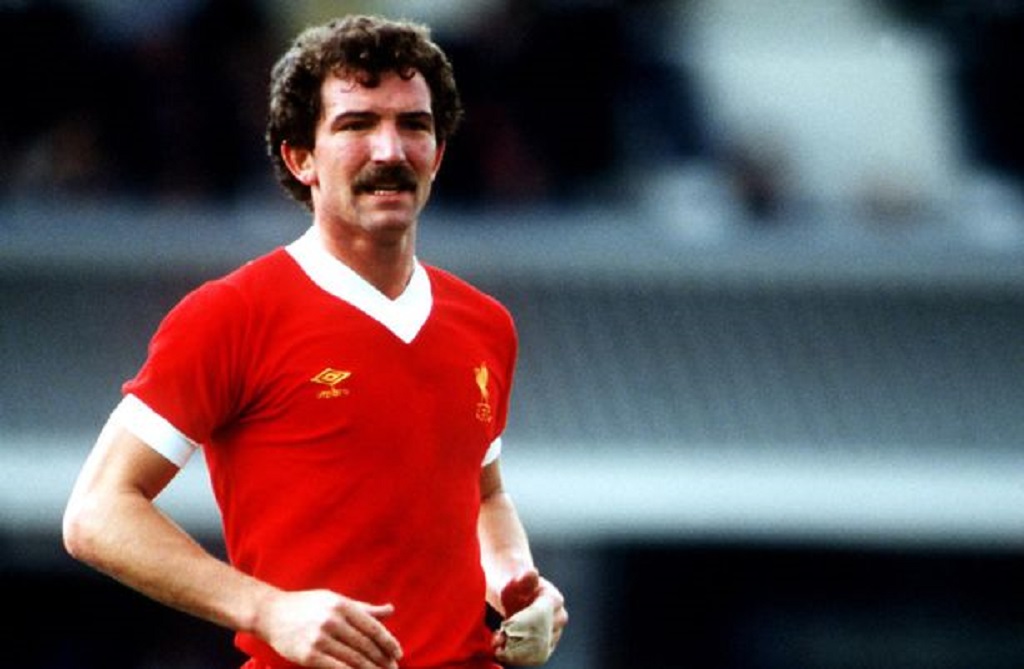

“Graeme Souness waited until the second half before he did Lyons,” recalls Lawrenson. “Cut his shin right open, but only got a yellow card. As Graeme walked past Mick he just said ‘That’s for Ray’.”

Tales of Souness’ savagery are legion, none recounted more often than the uppercut that broke the jaw of Dinamo Bucharest hatchetman Lica Movila in 1984.

The Romanians had spent the first leg at Anfield kicking anything that moved and the Scot’s patience finally snapped.

Souness was, without question, ‘that kind of player’. The kind of player who wanted to cause injury. The kind of player who left a mark, and did it on purpose.

If an opponent lay bleeding or concussed, you were 95 per cent certain he hadn’t “misjudged a challenge” or “tried to play the ball”. His violence wasn’t reckless. It was calculated.

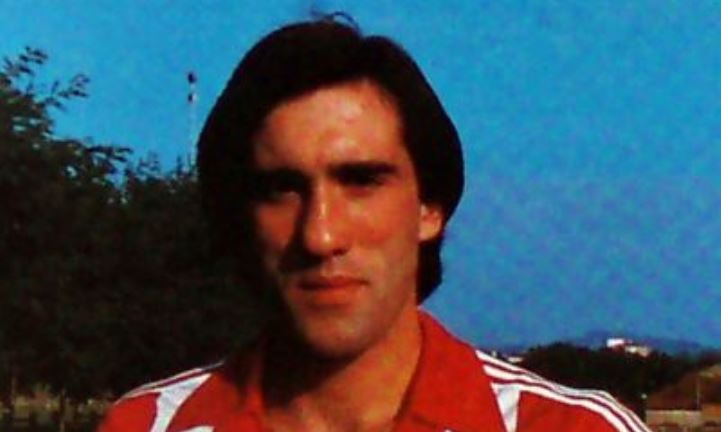

The same can be said of Andoni Goikoetxea, the infamous Butcher of Bilbao who robbed Bernd Schuster of an entire season and later framed the boots he used to break Maradona’s ankle.

Two decades of rule changes and an army of cameras have all but eradicated men like Souness and Goikoetxea, at least outside South America.

Not since the career-ending Kevin Muscat mercifully buggered off back to Australia has English football sheltered a bonafide thug in its midst.

So when Wales boss Chris Coleman stood before a TV camera and told the world that Neil Taylor “isn’t that kind of player”, nobody disagreed.

Deep down, we all know the Aston Villa full-back didn’t mean to hurt Seamus Coleman, let alone snap the Irishman’s right leg in such grotesque fashion.

We didn’t need Coleman’s protests. Nor the words of Welsh skipper Ashley Williams, who relayed how a devastated Taylor had desperately tried to contact his stricken opponent.

We knew it was a horrible accident – just like David Busst, Aaron Ramsey, Eduardo and all the other unfortunates left holding mangled limbs and oxygen masks. Taylor was reckless, but not violent.

The question is, does it matter? Should the punishment be based on intent, or on the damage inflicted?

The first is impossible to prove. The second is not. And if every player who inflicted a serious injury was hit with a serious sanction, the kind of recklessness that crippled Coleman would dwindle like the brutality of yesteryear.

Right now, if the ball spins loose and a 50-50 looms, a player can lunge in full tilt knowing the worst outcome – for him at least – is a red card and a three-game ban.

Raise that to ten matches for inflicting a significant injury and he’ll certainly think twice. Crucially, so would his opponent, removing any instinct for self-defence.

Gone, too, will be the hoary old ‘Well, if he didn’t go for it, the manager would have killed him’ justification.

Jem Karacan, the former Reading midfielder, still blames the blood ‘n’ thunder rhetoric of Neil Warnock for goading Michael Brown into the savage challenge that broke his ankle in April 2012.

The Turkish midfielder, now playing for League One Bolton after a miserable stint at Galatasaray, has since managed just 60 games in four-and-half seasons.

Andoni Goikoetxea, the man who famously framed the boots that broke Diego Maradona’s ankle

Whether Warnock was guilty or not, would any manager really insist on ‘getting stuck in’ if it cost him a key player for half a season? Hopefully not.

As for how any new regulation would work, let’s keep it simple. Initially, any player inflicting an injury that causes his opponent to leave the game (with the possible exception of concussion) should be dismissed.

If the injury proves to be minor, a one-game ban would suffice. More major – broken bones, ligament damage – and a disciplinary panel could then decide on a longer ban up to a maximum of ten matches. Harsh? In some cases it would be. But it is important to view this idea as preventative, not punitive.

The goal is not to punish broadly innocent offenders like Taylor. It is to prevent injuries to world-class players like Coleman by deterring reckless tackles at source. Wouldn’t the football world be richer for that?

And don’t give me any of this “The game’s gone, next you’ll outlaw tackling” bollocks that comes around every time somebody tries to protect players.

When did you ever see John Terry plough into a 50-50? Or Paolo Maldini? The best tacklers never get themselves into a position where winning the ball is a matter of chance. They anticipate movement, see patterns of play.

“The best defenders can smell danger before it arrives,” said Rio Ferdinand, another defender who rarely ended up on the deck.

“They position themselves in places that make it difficult for midfielders to play balls through gaps, or they step in front of a forward before a pass is even played so they can nick the ball off his toes.

“When I was a kid I had a coach who would tell me that if my shorts weren’t dirty at the end of the game then I’d not played well. In my mind, it’s the opposite. A good defender should be spotless.”

Precisely. This is not about banning slide tackles, aerial battles or any real physical element of the game. It is about discouraging recklessness.

Michael Brown, now manager at League Two Port Vale, was partial to a crunching challenge in his playing days

The fact is, a 50-50 is not what it was 30 years ago. Players are faster and physically stronger.

Assuming Taylor and Coleman were running full-tilt, you’re talking an impact speed of over 40mph. Why run that risk on a ball you might not win anyway?

What happened to Coleman benefits nobody. The player is out until 2018 and may never be the same again. Everton and the Republic of Ireland lost their best defender. Taylor is wracked with guilt.

Thirty years ago, we all worshipped ‘that kind of player’. Perceptions have changed, and for the better. Thirty years from now, it would be nice to think that people will look back on bone-rattling 50-50s with the same nostalgia.

*This article originally featured in the April/May edition of Late Tackle.